This zine/thkines bentcher was created for one of the many, many, many anti-zionist minyanim in Jerusalem. You can download the full meal version here. Please note that it does not contain Rosh Hashanah kiddush, hamotzi or handwashing brachot, so you’d need to BYO to use this practically.

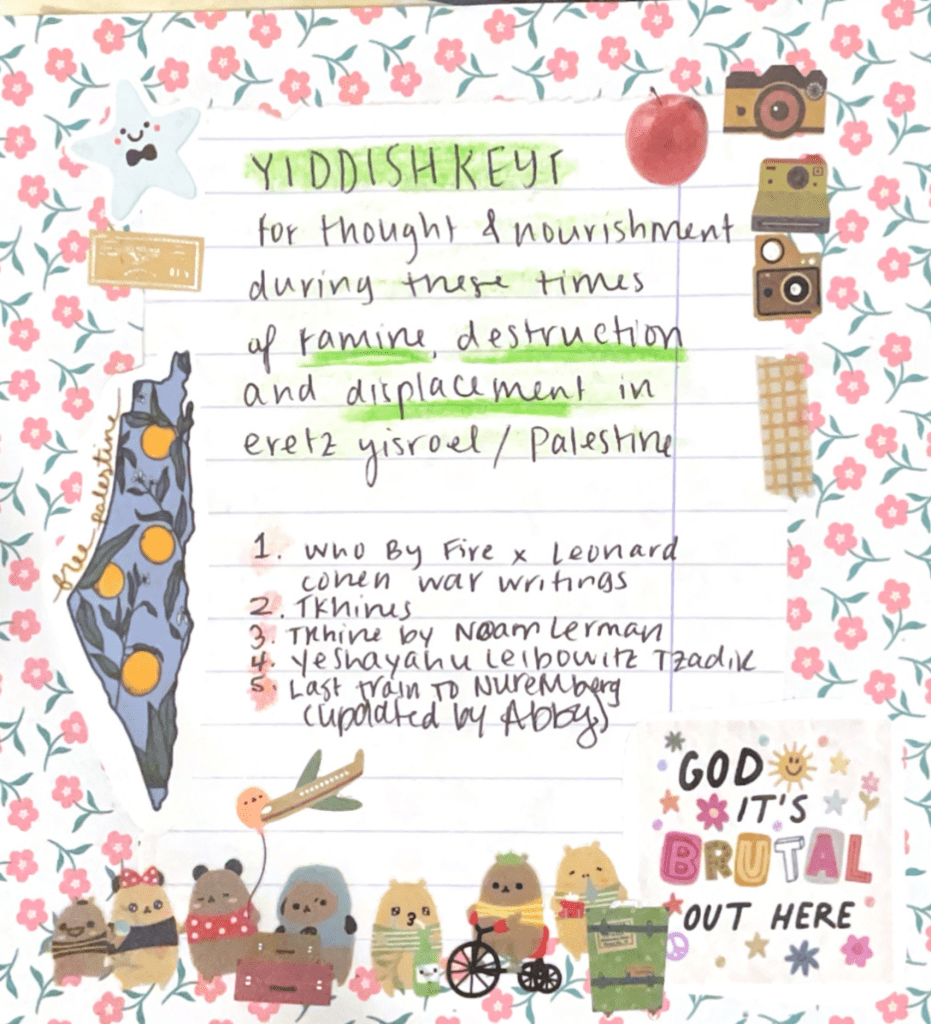

Title:

Yiddishkeyt for thought and nourishment during these times of famine, destruction and displacement in eretz yisroel/palestine

Table of Contents:

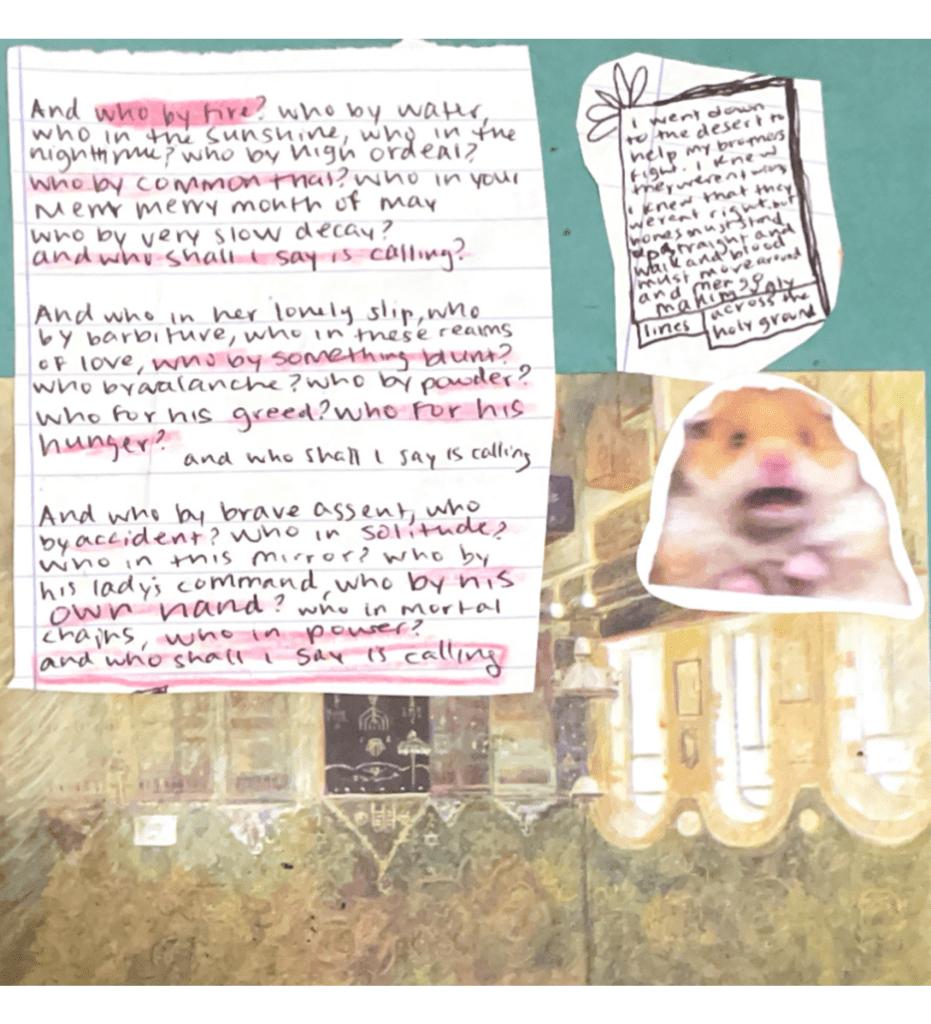

1. “Who By Fire” x Leonard Cohen lost war writings (1967, as printed in Matti Friedman’s book)

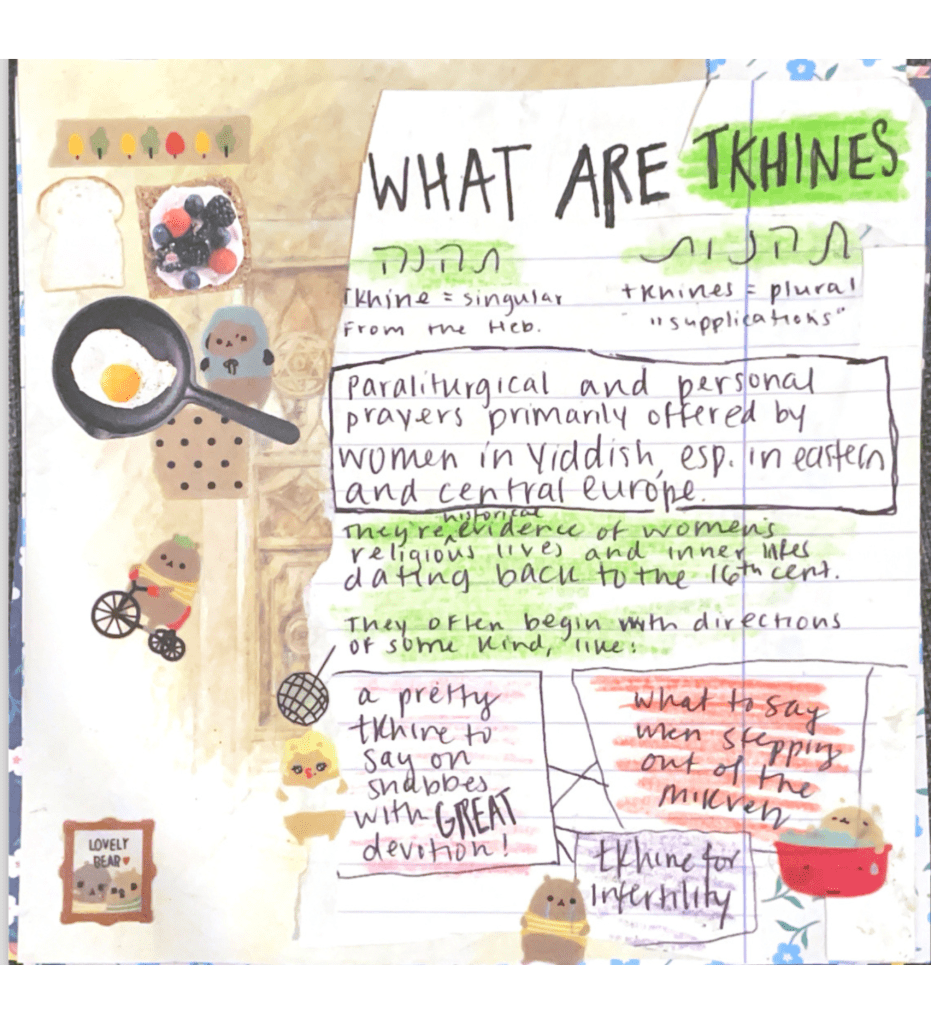

2. What Are Tkhines?

3. Original tkhine for Yeshayahu Leibowitz

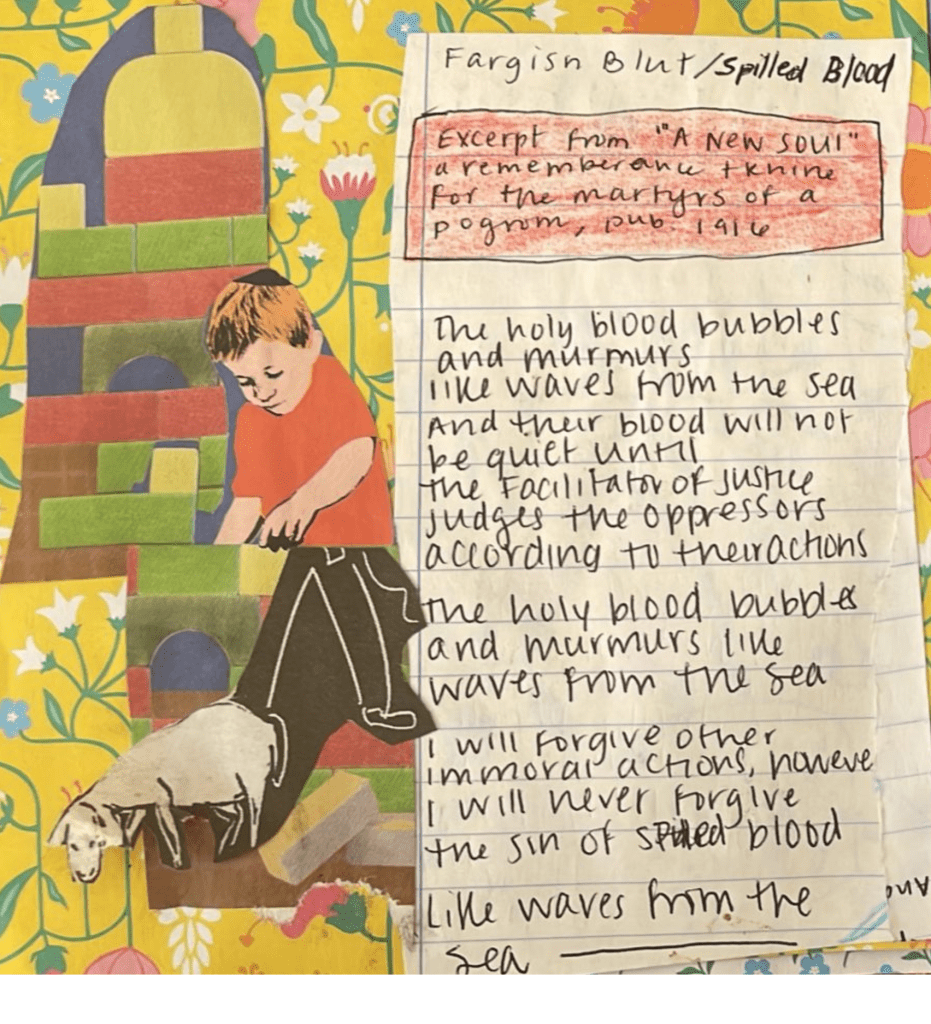

4. Spilled Blood/Fargisn Blut, a remembrance tkhine for the martyrs of a pogrom, pub. Vilna, 1916, in the collection “A New Soul.”

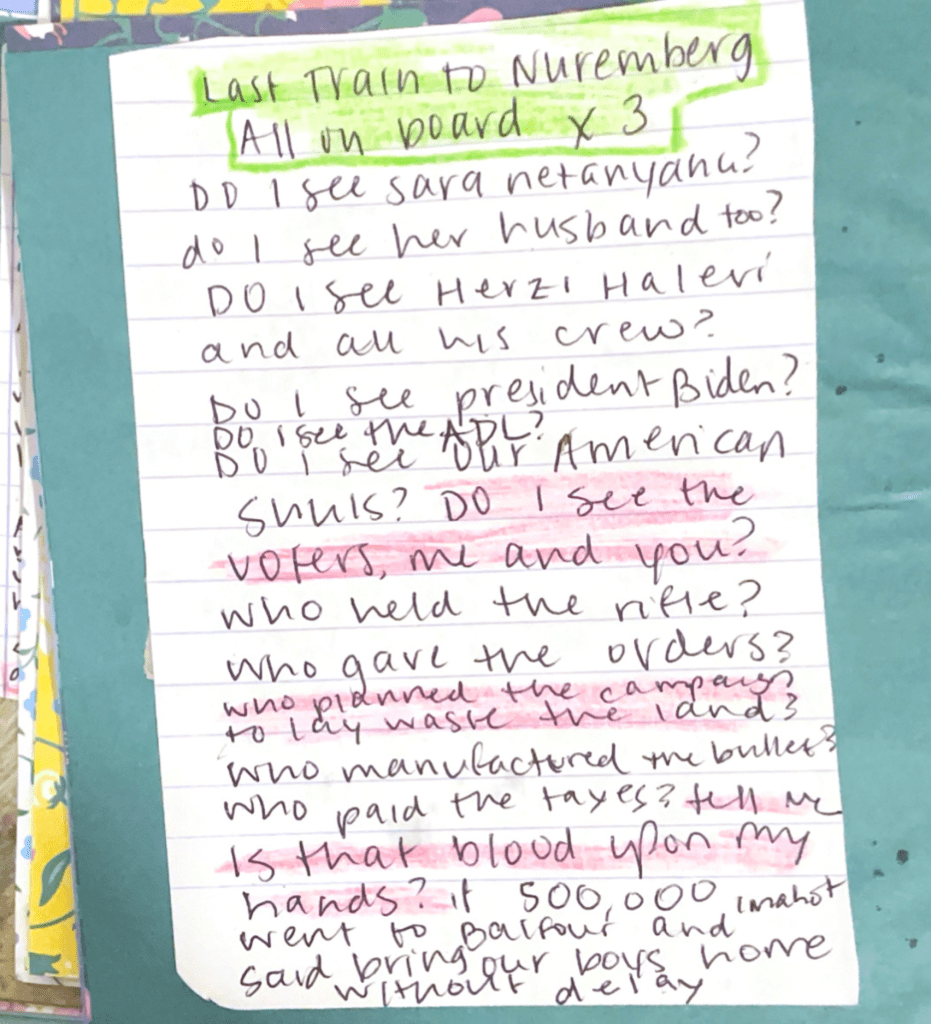

5. Updated verses of “Last Train to Nuremberg”

Mixed Media: stickers from Graphos in Nachlaot and Shams book cafe off Salah-a-Din, origami paper, colored pencil, pen, notebook paper, art postcards/sketches found on the streets of Nachlaot, glue stick, tape, cut-out from the print edition of this Haaretz article

Created by hand in one day during Elul 5784

In preparation for Rosh Hashanah night ii dinner, co-hosted by All That’s Left.

Artist’s statement

This thkines zine accompanied Boneh Yerushalyim’s Rosh Hashanah night ii bentcher/simanim. “Who By Fire” has long been appreciated by Jewish (North) Americans as significant Tishrei tune. Our trusted teacher Wikipedia explains:

“Who by Fire” explicitly relates to Cohen’s Jewish roots, echoing the words of the Unetanneh Tokef prayer and sung as a duet with Janis Ian (also Jewish; her birth name is Janis Eddy Fink).[10][11] The song was written after Cohen’s improvised concerts for Israeli soldiers in Sinai during the Yom Kippur War.[12]

Beside “Who By Fire,” I include another composition from Leonard Cohen’s gadna x wandering the desert stint. This lost verse of “Lover, Lover, Lover” that rolls around in my mind during times of increased bloodshed and profound grief.

“I went down to the desert to help my brothers fight

I knew that they weren’t wrong

I knew that they weren’t right

But bones must stand up straight and walk

And blood must move around

And men go making ugly lines

across the holy ground.”

The verse is recounted in Matti Friedman’s “Who by Fire: War, Atonement, and the Resurrection of Leonard Cohen.” The drama of the verse was first explained in this Times of Israel article prior to Friedman’s book release.

The first time I heard “Who By Fire” was in 2018, as a yeshiva bochura at the Conservative Yeshiva. At the time, I certainly could’ve been convinced that any any piece of secular culture composed by a Jew must have a valid midrashic intepretation. Years later, as I’ve frummed in and out, the tune remains a nostalgic comfort during Elul and through the Yamim HaNoraim.

Another late summer/early autumn practice of mine includes shuffling New Synagogue Project in DC, Nishmat Shoom, Kol Tzedek in Philadelphia, and the Queer Niggun Project. I have recently been spending a great deal of time in Central Asia, and niggunim are lovely lullabies for Uzbek sleeper trains. I was pleasantly surprised to find recently published melodies to try out this season: Tkhines in Song.

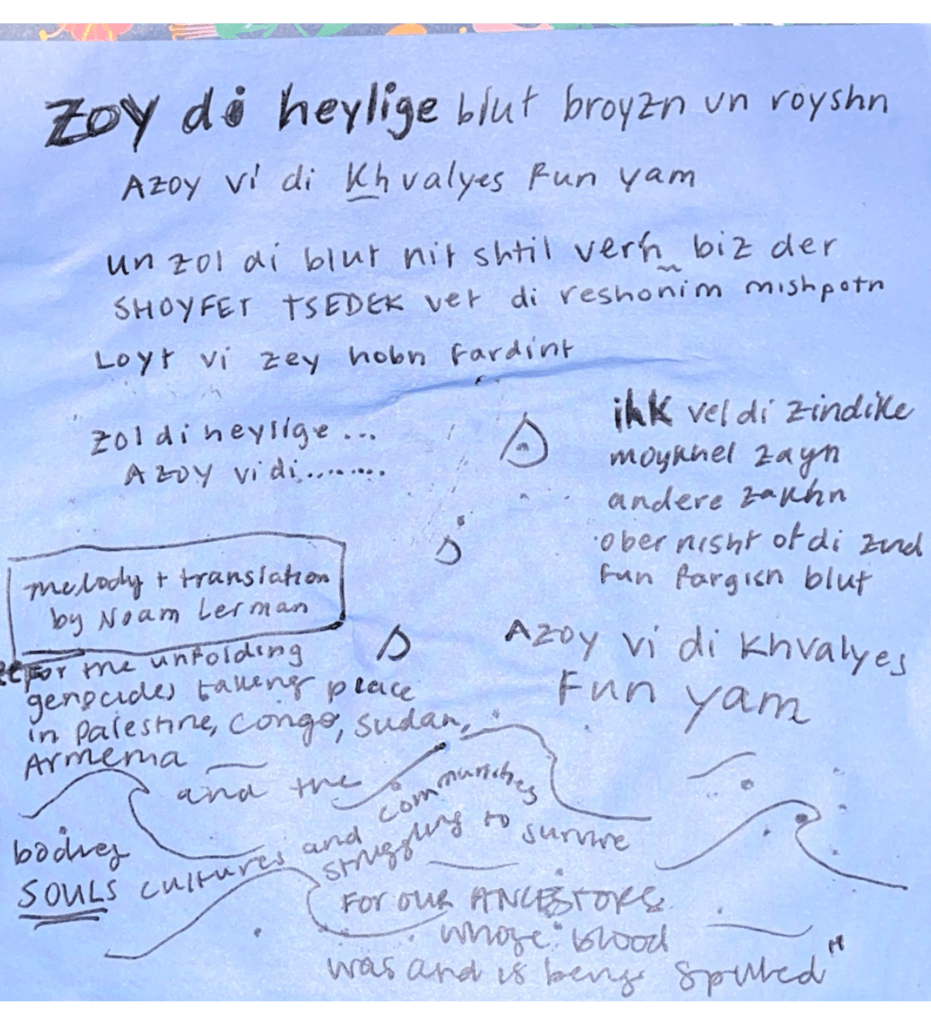

I was particularly moved by Noam Lerman’s singing of “Fargisn Blut,” a Yiddish tkhine meaning Spilled Blood.

Shas Tkhine Rav Peninim. Hebrew Publishing Company, published in 1916.

Excerpt from “A new soul-remembrance tkhine for the martyrs of a pogrom” p. 250.

For the unfolding genocides taking place in Palestine, Congo, Armenia, Sudan, and the bodies, souls, cultures and communities struggling to survive. For all our many ancestors whose blood was and is being spilled.

Melody and translation by Noam Lerman. Lyrics in Yiddish, transliterated Yiddish, and English:

זאָל די הייליגע בּלוט בּרויזען און רוישען (x3)

אזוי ווי די כוואַליעס פֿון יַם (x4)און זאָל די בּלוט ניט שטיל ווערן בּיז דער שופֵֿט צֶדֶק וועט די רְשָעים מִשְפָּט׳ן

לויט ווי זיי האָבן פֿאַרדינט (x4)זאָל די הייליגע בּלוט בּרויזען און רוישען

אזוי ווי די כוואַליעס פֿון יַם (x4)איך וועל די זינדיקע מוחל

זיין אַנדערע זאַכן,

אָבער נישט אויף די זינד פֿון פֿאַרגיסען בּלוט (x4)אזוי ווי די כוואַליעס פֿון יַם (x4)

Zol di heylige blut broyzn un royshn (x3)

Azoy vi di khvalyes fun yam (x4)Un zol di blut nit shtil ver’n biz der shoyfet tsedek vet di reshoim mishpot’n

Loyt vi zey hobn fardint (x4)Zol di heylige blut broyzn un royshn (x3)

Azoy vi di khvalyes fun yam (x4)Ikh vel di zindike moykhl

zayn andere zakhn,

Ober nisht of di zind fun fargisn blut (x4)Azoy vi di khvalyes fun yam (x4)

The holy blood bubbles and murmurs

like waves from the seaAnd their blood will not be quiet until

the Facilitator of Justice judges the oppressors according to their actionsThe holy blood bubbles and murmurs

like waves from the seaI will forgive other immoral actions, however I will never forgive the sin of spilled blood

Like waves from the sea

Waves, rumbles and rushing waters are powerful metaphors in Jewish art and life. I’ve poked around mikvehs (Jewish ritual baths) that served longstanding, often ancient communities in Greece, Macedonia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, Georgia, Czechia, Armenia and Uzbekistan that were attached like umbilical cords to a communal bath house, sometimes the river-facing part of the synagogue.

And of course, spilled blood is far from being a metaphor or Yiddish memory for Masafer Yatta, the Jordan Valley, and other rural Palestinian communities in the Occupied West Bank that carry on and survive under the constant threat of forced displacement, settler violence, and state brutality.

In addition to writing the tkhines explainer, I wrote my own tkhine for Yeshayahu Leibowitz:

The math professor tried to warn us that

“the idea that a specific country or location

has intrinsic holiness is an indubitably idolatrous idea”

and that “no nation has a right to any land”

if only we had listened to the brainy old man.

His turning point was the first invasion.

Now, we’re on the third.

He lived his life down the street until August 1994.

You may see his name and face on shirts that say “Leibowitz Tzadak,”

but the plaque outside his house is censored by the medina and its yetzer hara.

Leibowitz’s words, also included on his Wikipedia page, were originally recorded in an English translation of his essays entitled Judaism, Human Values, and the Jewish State (Harvard University Press, 1995). I wrote simple, short rhymes so that the meaning of the tkhine could be preserved if the tkhine were translated into another spoken language, which is essential to have in the kishkes of a tkhine.

The invasions refer to ground invasions of Lebanon. A nod to “Leibowitz tzadak” is necessary not only because my ben zug and I both own t-shirts with that slogan; I also wanted to pay tribute to an essential memory I carry around in my pocket. This slogan reappeared at Balfour on signs, stickers and shirts, and I misread it as “Leibowitz is a tzadik,” because I was, at the time, a subliterate American Jew who relied on vowels when reading.

I return to confront this inescapable Americanness by doing Mad-Libs on the final page. If you haven’t heard “Last Train to Nuremberg” in its original, listen to this:

Pete Seeger’s words sound a heck of a lot like lamentations. There are several times throughout a Jewish calendar when one may rely on lamentations found in the Tanakh (especially in the prophets), in Yiddish tkhines, in Judeo-Tajik proverbs, a blurring of boundaries because across the Diaspora, we preserved one scary truth: Lamentations don’t have to come from a book or scroll. They’re just one string and two cans. Me on one end, Hashem grasping the other can. In our grief, we find the strength to express our most honest words.

Last train to Nuremberg,

All on board! (x3)

Do I see Sara Netanyahu?

Do I see her hubby too?

Do I see Herzl Halevi and all his crew?

Do I see President Biden? Do I see the ADL? Do I see our American shuls?

Do I see the voters, me and you?

Who held the rifle? Who gave the orders?

Who planned the campaign to lay waste the land?

Who manufactured the bullet? Who paid the taxes?

Tell me, is this blood upon my hands?

If 500,000 imahot went to Washington and said

“bring our boys home” without delay

I ran out of room on the paper, so the song ended on a question. Ending on a question is great Jewish practice and poor writing practice. I prioritized maintaining Pete Seeger’s original words and spirit. His words were protests of the US’s role in the Vietnam War; the guests at the Boneh Yerushalyim dinner on the second night of the Jewish New Year needed to name our complicity as tax-paying Americans.

Critical to my general creative process/survival in the last year + then some has been the anti-war writings of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel z”l. In our youth, we accepted the conflation of medinat-am-ahavat-eretz-hahaganah yisrael in our normative American Jewish educations; similarly we must pay attention to when Heschel’s memory is evoked, by whom and where. For many years, our communities welcomed buzzwords like “social justice” “intersectionality” “diversity and inclusion” exclusively beside the photo of Rabbi Heschel marching in Selma as our rabbis exclaimed: di, nu, zehu, Ok already, that’s enough about segregation and dehumanization and militarization.

Speculating about what Heschel would say about the State of Israel or Herzl Halevi is not the point. Heschel’s anti-war writings are spiritually succinct and moving and inspiring, yes. The foundation of Heschel’s opposition to the Vietnam War were really just halakhic principles. Not obscure teshuvot, just derech eretz/common sense, radical amazement, a healthy dose of fearing G-d or something similarly Greater- Bigger-and-All-Knowing, and an unshakeable belief in the world to come.

I am grateful to the Baltimore-based Hinenu educator and artist Liora Ostroff who collected Heschel’s most precious anti-war writings into one Google doc. Her Instagram offers a glimpse into her recent work arranging Heschel’s words into amulets inspired by surviving Jewish artifacts of the past.

Throughout all of 5784, I did not feel like there was an abundance of new Jewish culture or Torah blossoming from dissent of the Israeli military and government. I live in Jerusalem, we don’t get the Holocausts playing here very often. Imbala is gone. It’s a desert for some of us.

I am forced to import the new Jewish culture. Jewish Currents’ Chevruta column and its foray into a weekly Torah portion in its Friday newsletter is total cunt. I was inspired by this Torah on despair penned by ATLer Aron Wander between the Jordan Valley and Boston. Domestic anti-war music is indeed emerging, as documented by that Haaretz hyperlink and this recent Disillusioned episode, created by Yahav Erez, a comrade of ATL and a talented storyteller.

As explained on page 2 of the bentcher and in this excellent Jewish Women’s Archive article, tkhines are a tested tool of survival through times of despair, destruction and chaos. Even if modge-podging some Jewish anti-war sentiments together will not single-handedly fix the world, I know I still can’t opt out from doing my part. So it goes.

Abby Seitz is a freelance writer and editor based in Jerusalem.

Leave a comment